IAIN A H-AON IAIN #1

|

| Caisteal Àrd Bhric |

I came back to my car after my wander round the castle soaked through but feeling good. There’s nothing like a cold shower to get shot of the last throes of

a hangover. I had a quick change of shirt before settling back into my seat

for the drive round to Loch an Inbhir

(Lochinver), where I hoped to do the same as I had in Melness. I didn’t have to

wait that long. The clues fell into place in a matter of an hour.

a hangover. I had a quick change of shirt before settling back into my seat

for the drive round to Loch an Inbhir

(Lochinver), where I hoped to do the same as I had in Melness. I didn’t have to

wait that long. The clues fell into place in a matter of an hour.

I first picked up a German hitchhiker who had

in fact been living in Scotland for a good couple of years and was part of the

local set-up. A cracking fellow, he took me straight to the house of Clarinda

Chant who helps out with local Gaelic classes, a lady who gave me a most courteous and helpful welcome and allowed me to try

the next link in the chain over the phone, fluent learner Claire Belshaw, to see if she had

any idea about surviving native speakers. I couldn’t get Claire, but Clarinda

did furnish me with an idea of how to reach a certain Iain “The Gate” MacCoinnich

(Iain MacKenzie) who was apparently a fluent Assynt native. I set off out of

Lochinver with time beginning to get pretty tight for my next appointment in An Dòrnaidh (Dornie) a few hours later.

I could make it though. I was in Rome and I was determined to meet some Romans.

in fact been living in Scotland for a good couple of years and was part of the

local set-up. A cracking fellow, he took me straight to the house of Clarinda

Chant who helps out with local Gaelic classes, a lady who gave me a most courteous and helpful welcome and allowed me to try

the next link in the chain over the phone, fluent learner Claire Belshaw, to see if she had

any idea about surviving native speakers. I couldn’t get Claire, but Clarinda

did furnish me with an idea of how to reach a certain Iain “The Gate” MacCoinnich

(Iain MacKenzie) who was apparently a fluent Assynt native. I set off out of

Lochinver with time beginning to get pretty tight for my next appointment in An Dòrnaidh (Dornie) a few hours later.

I could make it though. I was in Rome and I was determined to meet some Romans.

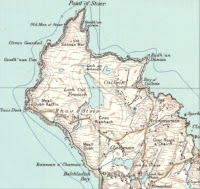

What happened after my initial success was that

I spent the following 45-60mins completely lost in amonsgt all the little roads

that intersect Rubh’ an Stòir (the Stoer

Peninsula). I was looking for a house close to the beach. I found one. I got

all the way down to it only to encounter a friendly chap at the door still in his

dressing gown and informing me pleasantly that he definitely wasn’t Iain the

Gate. I set off again through the sandy fields filled with trash, old cars and

rabbit holes and before I knew it I was out at the taigh-solais (lighthouse). Thighearna

Dhia (Lord God) I thought, this is another bloody ruith na cuthaige (cuckoo chase). I met a lady selling snacks and

drinks at the end of the road who did her best to re-direct me. She gave me a

sideways glance as I departed. I wondered whether I really looked that clueless. Quite possibly.

I spent the following 45-60mins completely lost in amonsgt all the little roads

that intersect Rubh’ an Stòir (the Stoer

Peninsula). I was looking for a house close to the beach. I found one. I got

all the way down to it only to encounter a friendly chap at the door still in his

dressing gown and informing me pleasantly that he definitely wasn’t Iain the

Gate. I set off again through the sandy fields filled with trash, old cars and

rabbit holes and before I knew it I was out at the taigh-solais (lighthouse). Thighearna

Dhia (Lord God) I thought, this is another bloody ruith na cuthaige (cuckoo chase). I met a lady selling snacks and

drinks at the end of the road who did her best to re-direct me. She gave me a

sideways glance as I departed. I wondered whether I really looked that clueless. Quite possibly.

Just at the point of thinking the game was a

bogey, I coasted down yet another hill and into Bail’ a’ Chladaich (The Shore Village) and what did

I see but a gate… next to a house plonked neatly into the sand with the

Atlantic not 200 yards away. Iain’s Gate. Iain the Gate’s gate. I got out and

stretched, thinking as always: cha

bhith e aig an taigh idir ann a-nis an déidh a’ ghnothaich seo uile! (of

course, he’s not going to be home now after all this business!).

bogey, I coasted down yet another hill and into Bail’ a’ Chladaich (The Shore Village) and what did

I see but a gate… next to a house plonked neatly into the sand with the

Atlantic not 200 yards away. Iain’s Gate. Iain the Gate’s gate. I got out and

stretched, thinking as always: cha

bhith e aig an taigh idir ann a-nis an déidh a’ ghnothaich seo uile! (of

course, he’s not going to be home now after all this business!).

I wandered round the side of the house and

chapped the door. Nobody came out. After all that. Bollocks to it. Then I heard

a faint sound of movement from the bowels of the house. It took a minute or

two, but Iain the Gate appeared at the door, looking relaxed but weather-beaten

from a life on the land. He settled his gaze on the stranger on the doorstep and

I hit him swiftly with my usual explanation of why I was there. So it was I met

Iain a h-Aon (Iain #1).

chapped the door. Nobody came out. After all that. Bollocks to it. Then I heard

a faint sound of movement from the bowels of the house. It took a minute or

two, but Iain the Gate appeared at the door, looking relaxed but weather-beaten

from a life on the land. He settled his gaze on the stranger on the doorstep and

I hit him swiftly with my usual explanation of why I was there. So it was I met

Iain a h-Aon (Iain #1).

Tha mi gabhail cuairt

a’ rùrachamh dhaoin’ aig a bheil Gàilig an àite, Iain (I’m taking a trip looking for

people who have the local Gaelic) I said, as Iain regarded me patiently.

a’ rùrachamh dhaoin’ aig a bheil Gàilig an àite, Iain (I’m taking a trip looking for

people who have the local Gaelic) I said, as Iain regarded me patiently.

Och, chan eil móran

Ghàilig agam·as

(oh I don’t have much Gaelic) he lied comedically with a slight smile.

Ghàilig agam·as

(oh I don’t have much Gaelic) he lied comedically with a slight smile.

Och! tha coltach gu

bheil gu leòr agaibh!

(oh! It seems like you have plenty!) I reply insistently.

bheil gu leòr agaibh!

(oh! It seems like you have plenty!) I reply insistently.

Ó, chan eil. Tha mi ‘fàs ro shean a-nis. Tha usa nad bhalach òg (oh no. I’m growing too old now. You’re a young lad).

Seo a’ chiad uair a chualaig mi Gàilig

Asainte gu ceart (this is the first time I heard Assynt Gaelic properly) I admit.

Asainte gu ceart (this is the first time I heard Assynt Gaelic properly) I admit.

Robh u seo roimhe? (were you here before?) Iain asks.

Cha do stad mi an uair

a bha sin (I didn’t

stop the last time) I concede before wondering Chaidh ur togail san dùthaich, nach deachaigh? (You were raised in

this country, weren’t you?) ‘N ann á seo

a bha ur pàrantan? (Was it from here your parents were?)

a bha sin (I didn’t

stop the last time) I concede before wondering Chaidh ur togail san dùthaich, nach deachaigh? (You were raised in

this country, weren’t you?) ‘N ann á seo

a bha ur pàrantan? (Was it from here your parents were?)

‘S ann gu dearbh (it certainly was).

Bheil crodh agaibh? (do you have cattle?).

Ó tha, tha ‘n dà chuid

agam. Crodh ‘s caoraich agam (Oh yes, I’ve both. I’ve cattle and sheep) says Iain. Inevitably, it

wasn’t long before my current obsession -finding out the names of the fingers-

reared its head. Nan hadn’t recalled the names for the MacKay Country, but

luckily they were in Seumas Grannd’s

book. Robh rann aca air na corragan?

(did they have a rhyme for the fingers?)

agam. Crodh ‘s caoraich agam (Oh yes, I’ve both. I’ve cattle and sheep) says Iain. Inevitably, it

wasn’t long before my current obsession -finding out the names of the fingers-

reared its head. Nan hadn’t recalled the names for the MacKay Country, but

luckily they were in Seumas Grannd’s

book. Robh rann aca air na corragan?

(did they have a rhyme for the fingers?)

Unfortunately Iain couldn’t bring them back to

mind either. Chan eil cuimhn’ agam air

sin. (I don’t remember that). Bha e

ann, ach cha bhith daoine ga bridhinn ‘s mar sin, tha mi ga call (It was

there, but people don’t speak it [Gaelic] now and so I’m losing it) Chan eil ach an aon duine ‘nis a bhitheas

ga bridhinn, Iain MacIllEathain an sin. (there’s only one man now who

speaks it and that’s Iain MacLean there) he said, motioning back the way with his head. Ma

théid u thigeas, gheobh u do leòr an sin (If you go towards him, you’ll get

your fill there). This sounded great. Mental note made to bring that name up

again if Iain didn’t. A question for me this time: Dé chanas tus’ air

do làmhan? Air an làmh seo? (What would you say on your hands? On this

hand?) asked Iain, gesturing with his right hand. An làmh cheart? (the right hand?) Sin a chanas aid sna h-Eileanan (that’s what they say in the Isles).

mind either. Chan eil cuimhn’ agam air

sin. (I don’t remember that). Bha e

ann, ach cha bhith daoine ga bridhinn ‘s mar sin, tha mi ga call (It was

there, but people don’t speak it [Gaelic] now and so I’m losing it) Chan eil ach an aon duine ‘nis a bhitheas

ga bridhinn, Iain MacIllEathain an sin. (there’s only one man now who

speaks it and that’s Iain MacLean there) he said, motioning back the way with his head. Ma

théid u thigeas, gheobh u do leòr an sin (If you go towards him, you’ll get

your fill there). This sounded great. Mental note made to bring that name up

again if Iain didn’t. A question for me this time: Dé chanas tus’ air

do làmhan? Air an làmh seo? (What would you say on your hands? On this

hand?) asked Iain, gesturing with his right hand. An làmh cheart? (the right hand?) Sin a chanas aid sna h-Eileanan (that’s what they say in the Isles).

An làmh dheas (the ready hand).

Ó sinne cuideachd (oh us too) says Iain, pleased. Bho chionn ghoirid, chuala mi air an television, “làmh cheart” ach an seo, ‘s

e “làmh dheas” a chanas aid. (I heard on the television, làmh cheart, but here, it’s làmh dheas that they’d say).

e “làmh dheas” a chanas aid. (I heard on the television, làmh cheart, but here, it’s làmh dheas that they’d say).

Dé their ead ris an

làmh eile? (What do

they say to the other hand?) I ask.

làmh eile? (What do

they say to the other hand?) I ask.

Làmh cheàrr (the wrong hand).

Gu dearbh? (really?) ‘S e “làmh chlì” a th’ againne. (It’s the “awkward hand” we have). Bheil facail eile anns an dùthaich a tha

car sònraichte? (are there other words in the country that are somewhat

special?) leithid, tha fhios agaibh, their

sinne “polladair” ris a’ bheothach sin a tha fanachd san talamh (the likes

of, you know, we say polladair [mudder] to

the beast that lives in the earth) mar a

their ead sa Bheurla, mole (as

they say in English, “mole”).

car sònraichte? (are there other words in the country that are somewhat

special?) leithid, tha fhios agaibh, their

sinne “polladair” ris a’ bheothach sin a tha fanachd san talamh (the likes

of, you know, we say polladair [mudder] to

the beast that lives in the earth) mar a

their ead sa Bheurla, mole (as

they say in English, “mole”).

Ó seadh, ‘s e famhan a

bh’ againn air sin

(oh aye, it’s famhan that we had on

that).

bh’ againn air sin

(oh aye, it’s famhan that we had on

that).

Dé theireamh ead ri spider? (What did they call a spider?). I adore this

kind of chat.

kind of chat.

Iain laughs and looks at me shaking his head. I

can tell he wants to sneak off and have a think about these! Ó hó hó he chuckles, cha do bhridhinn mi a leithid bhon a bha mi

òg! (I haven’t spoken its like since I was young!)

can tell he wants to sneak off and have a think about these! Ó hó hó he chuckles, cha do bhridhinn mi a leithid bhon a bha mi

òg! (I haven’t spoken its like since I was young!)

‘S e figheadair a

their ead an Arra-Gháidheil (they say figheadair

[weaver] to it in Argyll). I have never found the actual word for a spider in

the Dalriada dialect, but found figheadair

in Perthshire, Islay and South Lorn and having triangulated using those assume

that this word must at least have been known in Mid-Argyll. ‘S e figheadair-feòir a their ead ri h-aon mór, tha fhios agaibh, harvester (It’s figheadair-feòir [grass-weaver] that they say to a big one, you

know, a “harvester”).

their ead an Arra-Gháidheil (they say figheadair

[weaver] to it in Argyll). I have never found the actual word for a spider in

the Dalriada dialect, but found figheadair

in Perthshire, Islay and South Lorn and having triangulated using those assume

that this word must at least have been known in Mid-Argyll. ‘S e figheadair-feòir a their ead ri h-aon mór, tha fhios agaibh, harvester (It’s figheadair-feòir [grass-weaver] that they say to a big one, you

know, a “harvester”).

Ó seadh! (oh aye!) says Iain, clearly seeing

the sense in that expression.

the sense in that expression.

Having listened to a little Assynt Gaelic in Tobar an Dualchais, I had always

thought it was fairly close to the Lewis dialect. Perhaps not as close as Coigeach, but close enough. Feumaidh gu bheil a’ Ghàilig an seo, gu bheil i car coltach ri

Gàilig Leódhasach, nach eil? (The Gaelic here, it must be pretty similar

to Lewis Gaelic, eh?)

thought it was fairly close to the Lewis dialect. Perhaps not as close as Coigeach, but close enough. Feumaidh gu bheil a’ Ghàilig an seo, gu bheil i car coltach ri

Gàilig Leódhasach, nach eil? (The Gaelic here, it must be pretty similar

to Lewis Gaelic, eh?)

Tha, ó tha. (Yes, it is). Rudaigin faisg oirre (Something close to it). Anns an sgoil a-nis, bithidh aid a’ cunntadh (in the school now,

they will be counting) ach mar a chanas

sinne, ‘s e seachd ‘s ciad caoraich, no dà thar fhichead (but as we say, seven and a

hundred sheep, or two over twenty), ach

chan e sin a th’ ann a-nis (but it’s not that that’s there now). Despite the fact that the new manner of

counting is not actually a new system but a very old one and certainly less

confusing than trying to learn the multiplication of twenties which forms the

backbone of the old system, the new way is another departure from what native

dialect speakers understand, it’s another blockage in the road of the old folks

trying to reach the young and vice-versa.

they will be counting) ach mar a chanas

sinne, ‘s e seachd ‘s ciad caoraich, no dà thar fhichead (but as we say, seven and a

hundred sheep, or two over twenty), ach

chan e sin a th’ ann a-nis (but it’s not that that’s there now). Despite the fact that the new manner of

counting is not actually a new system but a very old one and certainly less

confusing than trying to learn the multiplication of twenties which forms the

backbone of the old system, the new way is another departure from what native

dialect speakers understand, it’s another blockage in the road of the old folks

trying to reach the young and vice-versa.

Tha an saoghal air

atharrachamh (the

world has changed) I say, with what I know to be a wry grin on my face. Iain

raises an eyebrow, as if I have understated the matter:

atharrachamh (the

world has changed) I say, with what I know to be a wry grin on my face. Iain

raises an eyebrow, as if I have understated the matter:

Chan eil e idir

mar a bha e (It’s not at all as it was). Tha an

seann ghinealach air falbh a-nis (the old generation are away now). A

statement made with obvious regret but a certain resigned acceptance.

mar a bha e (It’s not at all as it was). Tha an

seann ghinealach air falbh a-nis (the old generation are away now). A

statement made with obvious regret but a certain resigned acceptance.

Bha coltach gun

deachaidh gach rud atharrachamh anns an tir-mhór anns na seachdadan (It seems like everything changed

in the mainland in the 70s) I say, something I’ve heard many times from older

folk. Cha duair mi ‘n dearbh aobhar car-son a

dh’atharraich a h-uile gnothaichean, ach sin a their na sean-daoine sa h-uile

h-àit’ an Arra-Gháidheal (I didn’t get an exact reason why everything

changed, but that’s what the old folks say everywhere in Argyll). Thánaig na Goill a-staigh ‘s an sin cha

téid gas air ais thun mar a bha e a-chaoidh (The non-Gaels came in and then

nothing will ever go back to how it was).

deachaidh gach rud atharrachamh anns an tir-mhór anns na seachdadan (It seems like everything changed

in the mainland in the 70s) I say, something I’ve heard many times from older

folk. Cha duair mi ‘n dearbh aobhar car-son a

dh’atharraich a h-uile gnothaichean, ach sin a their na sean-daoine sa h-uile

h-àit’ an Arra-Gháidheal (I didn’t get an exact reason why everything

changed, but that’s what the old folks say everywhere in Argyll). Thánaig na Goill a-staigh ‘s an sin cha

téid gas air ais thun mar a bha e a-chaoidh (The non-Gaels came in and then

nothing will ever go back to how it was).

Ó sin agad e dìreach (oh there you have it exactly). Sin na thachair (That’s what happened).

Ach chan eil feadhainn òg’ ann an seo

ann (But there’s no young people here now whatsoever). Och, ach chan eil gin air fhàgail ga bridhinn ach MacIllEathain

(Oh there’s no-one left speaking it but MacLean). Excellent, Iain has brought up

MacLean again. Tha Gàilig mhath aige

(He’s got good Gaelic). Chaidh a thogail

le dà bhoireannach anns an taigh ‘s bha adsan a’ bridhinn Gàilig

an-comhnaidh (He was raised by two women in the house and they were speaking

Gaelic always). This is brilliant news.

Ach chan eil feadhainn òg’ ann an seo

ann (But there’s no young people here now whatsoever). Och, ach chan eil gin air fhàgail ga bridhinn ach MacIllEathain

(Oh there’s no-one left speaking it but MacLean). Excellent, Iain has brought up

MacLean again. Tha Gàilig mhath aige

(He’s got good Gaelic). Chaidh a thogail

le dà bhoireannach anns an taigh ‘s bha adsan a’ bridhinn Gàilig

an-comhnaidh (He was raised by two women in the house and they were speaking

Gaelic always). This is brilliant news.

|

| Bail’ a’ Chladaich le Aonghas MacDhomhaill |

‘S mar sin, thuair e a

h-uile facal (And

so, he got every word).

Thuair, sin agad e (He did, there you have it)

confirms Iain.

confirms Iain.

Agas am bith e ‘staigh

an ceartair? (And

will he be in just now?) I inquire.

an ceartair? (And

will he be in just now?) I inquire.

Ó shaoilinn gum bith,

shaoilinn gum bith

(Oh I would reckon he will be, yes).

shaoilinn gum bith

(Oh I would reckon he will be, yes).

Am bith sibhse agas

MacIllEathain, am bith sibhse bruidhinn na Gàilig dair a chì sibh a’ chéile? (Do you and MacLean, do you speak

Gaelic when you see one another?) I venture hopefully.

MacIllEathain, am bith sibhse bruidhinn na Gàilig dair a chì sibh a’ chéile? (Do you and MacLean, do you speak

Gaelic when you see one another?) I venture hopefully.

Ó bithidh, ó bithidh!

Mar as tric’, bithidh

(Oh we do, oh yes! More often than not, yes). And there you have it. No lack of

language loyalty from dialect speakers, as it is in Lismore and Ardnamurchan,

as it was with Noel Gow in Strathspey and Mrs Gallacher in Melness, just barely

anyone to speak to as the world moves on mercilessly and leaves behind the

jewel in the Scottish crown, the naturally occurring Gaelic language, while a

homogenised cardboard cut-out of it that was never actually spoken anywhere

usurps her throne.

Mar as tric’, bithidh

(Oh we do, oh yes! More often than not, yes). And there you have it. No lack of

language loyalty from dialect speakers, as it is in Lismore and Ardnamurchan,

as it was with Noel Gow in Strathspey and Mrs Gallacher in Melness, just barely

anyone to speak to as the world moves on mercilessly and leaves behind the

jewel in the Scottish crown, the naturally occurring Gaelic language, while a

homogenised cardboard cut-out of it that was never actually spoken anywhere

usurps her throne.

Och glé mhath, tha sin

gasta (oh very

good, that’s great). I am now aware that I have made a friend and with that happily

achieved and with time being what it is, I’d better go looking for MacLean. Cha chum mi air ais sibh ‘s sibh gabhail

fois Di-Domhnaich (I won’t keep you back and you relaxing on a Sunday). Is cinnteach, ma tha croit agaibh ‘s nair a

tha fois agaibh, bithidh sibh air son gabhail rithe! (For certain, if you

have a croft and you have some peace, you’ll want to accept it [ie go with it]!).

gasta (oh very

good, that’s great). I am now aware that I have made a friend and with that happily

achieved and with time being what it is, I’d better go looking for MacLean. Cha chum mi air ais sibh ‘s sibh gabhail

fois Di-Domhnaich (I won’t keep you back and you relaxing on a Sunday). Is cinnteach, ma tha croit agaibh ‘s nair a

tha fois agaibh, bithidh sibh air son gabhail rithe! (For certain, if you

have a croft and you have some peace, you’ll want to accept it [ie go with it]!).

Och seadh, gu leòr a

dh’obair ri dhianamh ach tha mi fàs ro shean a-nis (oh aye, plenty of work to be done but I’m

growing too old now). “Cha tig an aois

leotha fhéin”, mar a chanas aid! (“the age does not come alone” as they

say!). No, this is true. The sciatica down the back of my left leg that’s crept

in even just in my 30s attests to this. I don’t take for granted the fact that

the story of the body will get more complex as time wears on and as the old internal

engine wears down.

dh’obair ri dhianamh ach tha mi fàs ro shean a-nis (oh aye, plenty of work to be done but I’m

growing too old now). “Cha tig an aois

leotha fhéin”, mar a chanas aid! (“the age does not come alone” as they

say!). No, this is true. The sciatica down the back of my left leg that’s crept

in even just in my 30s attests to this. I don’t take for granted the fact that

the story of the body will get more complex as time wears on and as the old internal

engine wears down.

Bha fuathasach math ur

faicinn ‘s ma bhitheas mi san dùthaich, thig mi gur faicinn a-rithist (It was terribly good to see you

and if I’m in the country, I’ll come to see you again).

faicinn ‘s ma bhitheas mi san dùthaich, thig mi gur faicinn a-rithist (It was terribly good to see you

and if I’m in the country, I’ll come to see you again).

Ó latha sam bith! (oh any day!). Ma bhitheas tu air d’ ais a-rithist, thig a-staigh! (If

you’re back again, come in!). There’s the hospitality once again.

you’re back again, come in!). There’s the hospitality once again.

Shin agaibh na nì mi (there you have what I’ll do). An ath uair, theaga gun téid an dithist

againn a chéilidh air MacIllEathain ‘s bruidhnidh sinn Gàilig comhla (the

next time, maybe the two of us will go a-visiting on MacLean and we’ll speak

Gaelic together).

againn a chéilidh air MacIllEathain ‘s bruidhnidh sinn Gàilig comhla (the

next time, maybe the two of us will go a-visiting on MacLean and we’ll speak

Gaelic together).

Ó seadh, gu dearbh (Oh aye, indeed). A plan and a half.

Glé mhath, ciad taing

dhuibh ‘s slàn leibh

(very good, 100 thanks to you and health [be] with you). And with that, Iain

waves and watches as I nip round the wall and over to my car. I get in and

breathe a sigh of relief at having managed to continue my education despite the

hiccups. Whipping out my notepad again, I scribble pell-mell and in what is now

barely legible script the conversation topics we had and as much direct speech

as I can manage to recall before making for MacLean’s!

dhuibh ‘s slàn leibh

(very good, 100 thanks to you and health [be] with you). And with that, Iain

waves and watches as I nip round the wall and over to my car. I get in and

breathe a sigh of relief at having managed to continue my education despite the

hiccups. Whipping out my notepad again, I scribble pell-mell and in what is now

barely legible script the conversation topics we had and as much direct speech

as I can manage to recall before making for MacLean’s!

Brèagha!